Odd Nerdrum

by David Molesky

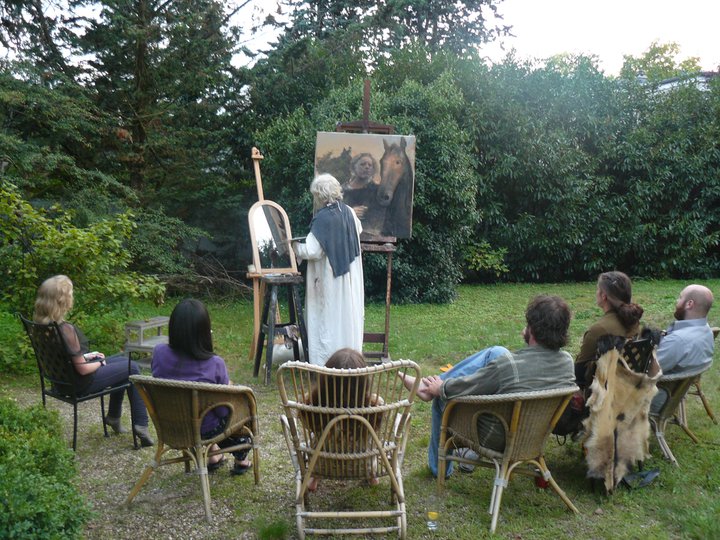

Odd Nerdrum working on a self portrait at his former home in Maison Lafitte outside of Paris.

A soft winter morning is broken by the rumble of a man clearing his throat outside in the courtyard. Then, a squeak of a door opening and … “BAM!” it slams. A moment later clogs accelerate up the steps, “Boom. Boom. Boomboomboomboom!“

This is the alarm clock for students at the Nerdrum academy.

Up the stairs, in the barn attic, is an environment clad in brown wood and crowded with enormous paintings on easels. There you can find the master seated in his chair, transfixing upon the painting before him, or working furiously – foam core palette in one hand, rag or brush in the other.

What comes across first, besides Odd Nerdrum’s strange appearance – his physical giantess, wild white-yellow hair and sack-like robes—is the intense focus that crackles in the room like electricity. Many a student has witnessed the man trip over a stool while backing up from a painting, never removing his eyes from the spot he is scrutinizing.

But the studio is also full of conversation and laughter. Odd is a gifted storyteller and knows how to stoke and provoke his students. As he works, he coordinates entertaining debates, spiked with Norwinglish aphorisms to illustrate his points. For example, when he says, “The life of a hero: He did not search for his reflection in the eyes of others,” or “You must go into a dark cave and look for a small dark flame,” he is speaking about the journey of someone deeply dedicated to their craft.

Each year, students from all over the world write to the Nerdrums requesting the opportunity to study with Odd, who has been called “the practical keeper of the grand tradition of European painting.” Odd’s stature is no fluke of history either, but rather the product of a focused will on a singular intention. At age 14, Odd made a decision that he would spend his life striving to paint as well as Rembrandt.

Odd’s earlier work concentrated on portraits, and like Rembrandt, Odd is well known for paintings of himself in various roles. When a new student arrives, a suggestion from Odd to paint a self-portrait is soon to follow. Why? “Painting yourself is the cheapest model you can get. A lot of painters excuse themselves by painting from photographs, and this limits the learning process. But if you paint self-portraits very well, people will admire your work and then it will be easy for you to find models.”

In fact, Odd paints strictly from life and his imagination. He does this even when painting large beasts like horses, which can get pretty hairy, as you may imagine. “I have seen a lot of fine pictures from photos,” he says. “But the greatest talents in this world have never painted from lenses of any kind. Rembrandt and Leonardo Da Vinci avoided the camera problem. They felt that it was a sort of prison. Many others from their time used photography, and sometimes very well. But it is much more voluptuous to observe nature with your own eyes.”

Throughout the workday, Odd takes short pauses to sip coffee and engage with his audience. He turns towards his students, offering advice to the young figurative painter on how to navigate a world full of snare traps and challenges. “If your only goal is to ‘find yourself’ and be ‘original’, you will end up in an empty, dark room. Those common commandments are misleading. Instead, find a master from the history of painting; a master that fits your own personality. For example, a pupil of mine looked like El Greco. I said to him, ‘go to the old master, El Greco and do the same as he did.’ Now he is a fine painter. I see daily improvement.”

Passing down traditions and techniques is part of cycle. Odd transmits learnings back to his students based on his own nurturing relationship to older artists. “I’ve had one mentor in Norway and one in America. In Norway it was a sculptor named Joseph Grimeland, and in America, the painter Andrew Wyeth. I have said to some of my young students that to have contact with people from all ages gives you a greater perspective, a greater sense of volume.”

Odd works to develop in his students a regard for the infinite that will allow them to command the helm of their own artistic path with confidence and without fear. “The most important thing, the thing of highest value is something that no one can really articulate. But you can experience it yourself. Go to a foreign culture, and you will feel you are in a void. There, is the quality that you will find in all the greatest masterpieces in the world. You hear no news from your home-state, you are far away from your hometown. Eternal feelings for eternal values are the greatest achievement. Maybe you will get lonesome, maybe you are not bound to the social chain gang. But you feel alive in a strange, dangerous world.”

Ultimately an artist/painter must form a hierarchy of values, a platform from which to evaluate and differentiate the perceived exceptional qualities in pictures. Odd explains,

You have three dimensions: The first one is the egocentric level. Most of the artists today are in that group. They want to find themselves and at the same time be a part of the modern society. Therefore, they are not responsible for the knowledge from the past. They are, in some ways, the only ones born in all of history, and look at everything with a child’s eyes: ‘everything is for me.’

The next level is the geocentric. The artist sees the world around him and tries in earnest to paint it beautifully. Everything in nature has the same value and must be rendered with taste and beauty. It’s about being absolutely natural; using the measure stick. The perspective must be nice and you must know a lot about anatomy. Be true to the truth and make a fine finished picture.

The next, and highest level is the heliocentric. If we study Plato, he says that Nature is merely a copy of an unseen world. Perhaps Plato saw a glimpse of the hidden world. When we look at planets, we see that there is space between them. All the forms are round. There are no stiff lines in the universe. The human body is about the same, it has round sensual forms. Therefore, those who study the past will feel that there is no time or any place, just volumes in the void. Because Rembrandt has this quality, his last portraits are so wonderful. Some reach this level late in life. Da Vinci is a typical example of a heliocentric person.

Beauty is a heliocentric idea. In the western world, beauty was discovered by the Greeks. Why everybody is searching for beauty is because it has a little bit of the heliocentric desire in it. The planets move according to circles. In composition, the circle frees the mind so one can work on the composition with joy. If we compare a good heliocentric work with a good geocentric work, you have no choice, there is only one answer: the circles smile to you.”

Recognized in his own country early as a prodigy, all eyes fell on Odd as he repeatedly provoked the press with his counter-current viewpoints. Norway’s discovery of oil in the North Sea during the late 60’s ended the country’s long era as a simple fishing nation and rapidly transformed it into one of the wealthiest in the world. Norwegian cultural authorities wished to produce a modern artist who could compete in the booming international abstract expressionist movement. This would be another feather in Norway’s cap, showing the rest of the modern world it had arrived.

During this time, and while in his early 20s, Odd entered two paintings into the annual National Salon, a juried exhibition to survey contemporary art: he entered the first – “a loose painting looking a little bit like G. Roualt”– under a fictitious name; the second was a portrait distinctly Nerdrum. The loose painting won first prize. When the crowd at the award ceremony looked about for this newcomer, who’d so suddenly and noiselessly snuck upon their most distinguished scene, all they found was Odd chuckling in the rows. It was too much! Several of the older painters were spurred to rage when they realized the mocking prank. They grabbed Odd and dragged him into a bathroom and dunked his head into a toilet several times before throwing him out the window into chest-deep snow.

Odd summarizes his rejection of modernism, to walk a less popular path, “I don’t like large crowds, I prefer to know one individual at a time.” After being chased out of the Oslo Academy of Art, “like a mangy dog,” Odd entered the Dusseldorf Academy, and studied with Joseph Bueys. The art department was full of conceptual artists, and the few painters there worked in abstraction. Students in the school nick-named him Zorn, the German word for wrath, but also the name of the turn-of-the-century Swedish painter known for voluptuous figures. When a fellow student asked Odd to participate in a performance piece to symbolize the end of painting – which included a gun drawn and pointed at Odd’s head — he realized that an academic environment is not the place to pursue his practice.

“I have felt all my life that I have been in exile. My sons and I are making a book about this now, entitled ‘Crime and Refuge.’ I don’t like civilization’s new friend Prozac. A civilized man of today no longer knows of Phidias or Homer. I’ve been persistently attacked by that sort of civilization. Therefore, I like to be in company with very few people, that I can ‘trust a little’.”

Recently, to the shock of much of the art world, Odd was sentenced to prison for tax fraud. It is a heavy sentence – nearly three years in jail. (By comparison, Norwegian extremist Anders Brevik, born 1979, who killed 77 children and adults in cold blood, received 21 years, roughly 3 months per life taken.) Luckily, the Norwegian Supreme Court revoked this judgment early this year. The case will be retried using the new evidence that supports Odd’s claim that he was taxed multiple times for the same income.

Nearly a century ago, Norway leveled similar accusations against the painter of the iconic Scream. Is this a coincidence? Or is there a deeper meaning, perhaps linked to the Norwegian socialist character and government that frowns upon any citizen rising head and shoulders above the rest? “Concerning Munch, it’s correct that he had severe problems with the Norwegian tax authorities. They were working on him for twenty years. But when the second World War started, the inquisition became silent and for his last four years, he was released into happiness.”

The strife faced by both Odd and Munch arguably served as a kind of fuel for their creative engines. What would Odd’s work be like if the Norwegian public and media didn’t paint him as a boogey man, making him look like a blond Dracula with their paparazzi tabloid photography? As much as Odd resists the politics and philosophies of the dominant paradigm, he has deep pride in the heritage of his Nordic culture. “The problem is not the people, it’s the government. But if you are beaten badly by your mother, she is your mother after all, and you excuse her again and again.”

Odd’s charge against the dominant current has resonated through the world, as a large boat creates waves from its bow. This inspiration has largely fallen on the shores of the America’s, where a growing contingent of painters are following his lead in their strides to paint emotionally charged narratives. Odd acknowledges, “There’s an impressive movement happening in America. Many young people are working in the styles of the great masters and some of them are extremely courageous.”