In A Larger Moment: David Molesky’s Painterly Allegories of Being

by Mark Van Proyen

Not so long ago, painters would often say that they found their images and ideas “in the paint,” meaning that they had a sufficient faith in the power of spontaneous improvisation so as to feel no need for any preconception before starting any given work. It was only after the influence of conceptual art had been felt did painters start to resort to those terminological enhancements called “artist’s statements” as a way of organizing their efforts. The jury is still out as to whether this shift in focus can be said to have improved the painter’s art in any measurable way. Painting needs to be painting before it can be other things such as decoration, illustration or metaphysics, and this is true simply because the problem of tangible embodiment always has to be solved in a tangible way. Some painters ignore this fundamental problem at the peril of their art, regardless of any other considerations that their work might deserve.

Even the most cursory look at David Molesky’s paintings tells us that he is fully invested in the physical tangibility of paint as it relates to the psychological tangibility of the myriad subjects that populate his work. Over the years, these have ranged widely, running the gamut from thickly painted abstractions to fantastic, quasi-mythical landscapes, and on to solitary human figures executed in the kind of thick impasto brushstrokes of the type that have come to be associated with Bay Area Figuration. But every time that Molesky takes on any subject, he always makes it his own by way of an unmistakable painterly touch. It is something akin to a Midas touch and something that cannot be taught—it is, in fact, a sign of the confident grace that emanates from an untroubled mind that is capable of fully being in any given moment where his paintbrush conveys pigment to any waiting surface.

It is worth noting that Molesky has done a great amount of traveling, mostly in Europe, and this is especially impressive considering the fact that he is still in his early thirties. He has spent extensive periods of time working in Austria, Poland, France and Italy, which has given him a first-hand familiarity with a great sampling of the grand tradition of European painting, as well as the complex cultural habitats that frame the local understanding of that tradition as an extended family history. This leads us to an important point to be made about Molesky’s work, in that it bespeaks an almost completely unmediated relationship to the historical practice of painting, one that is uncontaminated by the way that the mass media skews and dilutes the experience of that tradition. Whereas most American painters of Molesky’s generation have chosen to position their work in relation to the various pop media clichés that are loosely arrayed beneath the shopworn banner of Pop Surrealism (for example, the artists championed by the publication Juxtapoz), Molesky has instead aligned his practice with the mythopoetic wellsprings that have sustained painterly embodiment as a primary mode of cultural self-understanding for over 500 years. Along with that position come the analogies that can be drawn between painting as a composite layering of colored surfaces and individual subjectivity as a composite layering of experience. Both need to take place in their own time and at their own pace, even if the demands of the world that surrounds them always call for more velocity, more efficiency and, above all, more abbreviation—that being coded communication called by a more descriptive name. Whereas many artists make their work to reflect and accommodate those calls, Molesky’s reverses that polarity by making paintings that slowly reveal themselves to the viewer. By insisting on a slow, gradually unfolding revelation of their semi-secret contents, his paintings remind the viewer of the truism that “life happens pretty fast—if you don’t slow down once in a while, you might miss it.”

Molesky cites an art teacher named Walt Bartman as being a positive influence during the time that he attended the Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland— a school that had gained significant national acclaim in the early-middle 1990s for harboring a consistently high level of artistic accomplishment. It is worth noting that Bartman studied with Wolf Kahn, an artist world renown for his chromatically saturated landscapes, locating Molesky’s own interest in painting the land within a longstanding tradition. But even at that early age, Molesky was signaled out for his artistic abilities and heralded as something of a golden boy, selling quite a few paintings when he was a teenager. He eventually landed at UC Berkeley, completing both a pre-med sequence and a degree in Art Practice in 1999. After that, there was more travel, with extended stays in Austria, France and Poland.

Perhaps most significantly, from 2006 to 2008, he apprenticed with Odd Nerdrum in both Norway and Iceland. Nerdrum is an internationally recognized artist who has adopted the old master techniques of Rembrandt and Casper David Friedrich to make compelling allegorical images of the starkest aspects of the human condition, and more than anyone alive today, he is the practical keeper of the grand tradition of European painting. He is the senior living practitioner of what art critic Donald Kuspit has called “The New Old Masterism,” a recent phenomena in contemporary painting that willfully turns its back on a now over-institutionalized (pseudo) avant-garde art that has degenerated into tourist-oriented “postart” spectacle. The premise of New Old Master art is that painters can synthesize modern content and traditional technique to make images that give a unique dramatic form to post-modern consciousness. As Kuspit writes, “New Old Master art brings us a fresh sense of the purposefulness of art—faith in the possibility of making a new aesthetic harmony out of the tragedy of life without falsifying it—and a new sense of art’s interhumanity.”(1)

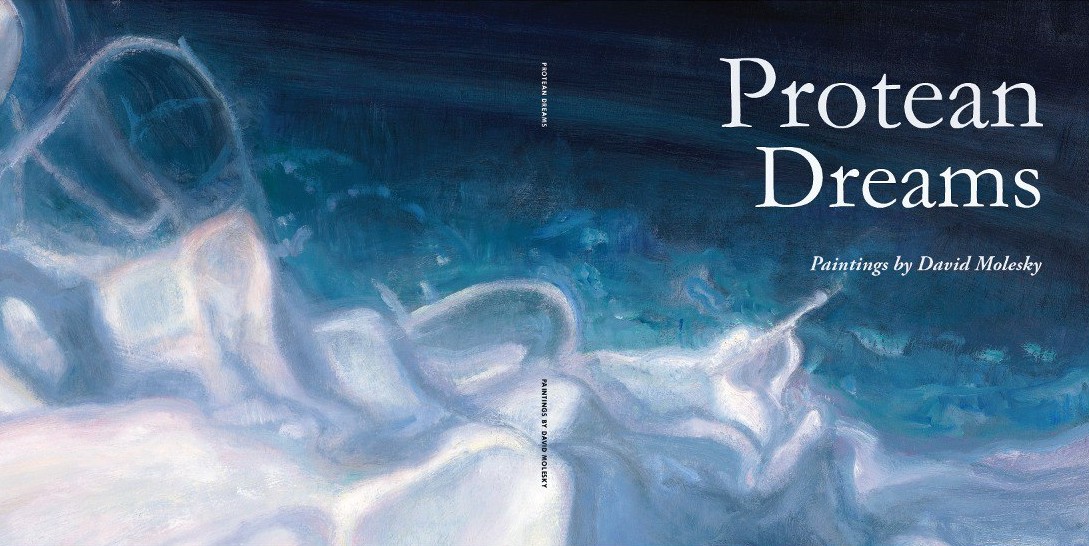

It is clear that Molesky learned a great deal from his sojourn in the northern climes in general and from Nerdrum in particular. Many of the subjects that he has chosen to paint during and immediately after his apprenticeship show telltale signs of Nerdrum’s influence, for example, the Wagnerian theme of Man Running In the Forest, in the billowing clouds featured in Chasing Tails and Geysir (all 2008). That influence also goes beyond subject matter and into the realm of style, as is evidenced in the way that Molesky paints some of his landscapes as vast impersonal spaces suffused with a crisp Nordic light. But some of the other landscapes start to show Molesky slowly breaking away from Nerdrum’s influence, particularly those that portray surging ocean waves as their primary subject. These works might seem to be picturesque at first glance, but closer inspection has them being something very different. As is revealed in works such as Harvest the Excess or Punch Bowl (both 2010), Molesky’s wave paintings reveal themselves to be lush and lavish fantasies that explore complex Baroque notions of form understood as being the kind of spaces that fold back upon themselves to reveal hidden realms of visual surprise as well as the stunning, gem-like luster of the oil paint used to describe them. We might remember that the word Baroque was originally derived from the Portuguese term that describes an irregular pearl, and that it quickly took up a memorable art historical residence when it was used to describe the dramatically folded spaces of Bernini’s saintly sculpture and the grandiose and opulent ecclesiastical architecture of the 16th century. Working with these narrow guidelines, it seems clear that the only well-known painter whose work truly earned the ascription “baroque” was Peter Paul Rubens, as most of his contemporaries should more rightly be called mannerists if they were from southern Europe, or allegorical naturalists if they were from the north. It is also worth mentioning that there is something of a baroque current that runs through that genre of still-life painting called banquet scenes. These usually feature close views of table tops supporting opulent assortments of exotic food that simultaneously seem intriguing and even a bit disgusting, slyly bespeaking a time and a world view where colonial enterprise had made gluttony a topic of ambivalent cultural reflection.

I bring this up because many of Molesky’s post-2010 wave paintings are so distinctly Rubenesque, doing something similarly lavish for the archetypal elements of elemental forces as Rubens did to the human form. Clearly, both artists make an equation of the sumptuousness of oil paint with human flesh, although Molesky extends that equation to the fleshiness of the entire world that he paints. This is not simply an expedient equation of subject and portrayal, but rather something that is its reversal, as he has chosen subject matter that in various ways can be taken as allegories for the alchemical processes and psychological dilemmas that come part-and-parcel with the painter’s art. In other words, his work tells visual stories about the challenges of visual storytelling, and they do it a great deal of style and finesse that seizes on the drama of air and water as signifiers for two of the four cardinal modalities of nature itself. Thus, it was only a matter of time before earth would be added to Molesky’s roster of artistic themes, because, concurrent with the wave paintings, he had already addressed the subject of a world on fire.

At one rather telling point after the financial crisis of 2008-2009, Molesky focused his painterly attention on a series of nocturnal images of large wildfires burning in the Hollywood Hills, as is exemplified by paintings such as La Crescenta (2009). These are uniquely stunning works, not just for their apocalyptic take on recent events, but also in their almost perverse articulation of the sublime beauty that underlies tragic events. From the standpoint of pictorial realism, fire is one of the most difficult things to paint, which is why it so often looks so over-stylized in many artists’ work. This is not the case for Molesky, who thoroughly nails the realistic look of terrifying conflagration while also grasping its sublime character with a kind of philosophical detachment. These works are brilliant expositions of the power of bright red and orange glowing against a dark background, calling to mind an apocalyptic tradition in painting that stretches back to Bosch and Breughel, as well as to our daily barrage of media images of oil well fires and military airstrikes.

All of this leads to the most recent works in this exhibition, which show Molesky turning his artistic attention to the earthly elements, but with a unique and innovative twist that gives us hints of something that only vaguely resembles the human figure. These paintings seem to have naturally evolved out of the paintings of clouds and waves, but they are also much less specific, almost non-objective in a way that connects to earlier abstract paintings such as Electric Water Lilies or Featherbed (both from 1999). The earlier works show Molesky exploring both the potential for and the negation of pictorial differentiation that naturally inhabits painterly substance, suggesting a condition of formless primordiality. Yet, in the recent works, something specific starts to emerge from the painterly fields. Take, for example, the large painting titled Eclipse of an Under Current (2011). Here, you will see a complex yellowish shape that suggestively resembles glowing lichen centrally located against a cluster of less distinct bluish shapes that teem with subdued energy. Look closely at the yellow form and you will note that it bears a vague resemblance to a human figure, albeit one that has become a kind of octopussian way-station for multiple visual networks of fantastic baroque forms. Some of its facets seem to be demons forming themselves out of the earth’s clay, perhaps representing some new form of damned soul that can only observe its own slow decomposition into undifferentiated form, retaining but a dim memory of an autonomy that was lost long ago. This work, and its close cousin titled Etheric Impulse from 2010 do something very innovative: they portray the human figure in a state of having been almost completely dissolved into its multiple connections to its complex environment—this being a distinctly 21st century rejoinder to the 20th century idea of the figure revealed as the singular existential actor taking a position of anxious nobility in the great tradition of western portraiture.

Granted, my reading of these works as having a figurative subtest may err on the side of being too imaginative. But given the reality of what psychoanalysts call “projective identification,” it is common enough to imagine that we see the shapes of figures and faces suggested by cloud configurations or the rhythmic leap of flames. Ever since the time of Leonardo, painters have toyed with this psychological phenomena to translate hallucinations into visible fantasies. Molesky’s most recent work follows in that tradition. His version of it carries a uniquely 21st century spin that redefines the traumas that threaten the illusion of autonomous selfhood upheld by earlier figure and portrait painters. Allow me to clarify: figure painting in the 20th century tended to reveal the self as a tragic-comic antagonist to a world drenched in violent upheaval; think of the examples of Cubism, Pre-war German expressionism and the terrifying figures painted by Francis Bacon and Willem De Kooning. These are figures that seem to nervously expect a sudden trauma that would forever rupture the tenuous structures of their self-experience, leading to the anticipation of a sudden psychological disintegration. We should remember that the 20th Century was one of dramatic technological and political upheaval that reshaped the rules that govern social relations, and to a certain extent, subjectivity itself. Given such a legacy of disruption, using the human figure as a lightning rod for exaggerated anxiety (or the triumph over anxiety) could be understood as an existentialist antidote to the social upheavals that were and continue to be a common feature of everyday experience. But it seems that the tale of the 21st century will emphasize other modalities of experience, leading to other ways of using figural forms to address new anxieties.

It is now clear that the 21st century will become the age of the electronic network, meaning that the most terrifying things on our horizon of fear may no longer be nuclear devastation. In its place live the more insidious possibilities of cybernetic viruses that can cripple the automatic servomechanisms upon which we all depend, or biological weapons that can decimate whole populations without revealing who might have put them into play. Certainly, these are extreme illustrations, but they are now possible in a way that was unimaginable even a decade ago, and in any event, we don’t need to resort to them to make the point about the new age of the network defining 21st century experience. All we need to do to confirm this fact is to look at recent political upheavals in the Middle East, caused in no small part by the fact that instantaneous communications technology now makes it impossible for dictatorial political regimes to control the flow of information. Indeed, the new fears are not the same as the old—biological weapons and computer viruses are the new bête noirs of our century’s imaginary apocalypse, replacing the mushroom clouds of yore. That much being said, we might then ask a somewhat more delicate question: what does this new age of networks do to the introspective solitary self that has been at the mythical center of artistic creation since the time of Rembrandt? As has already been mentioned, the 20th century witnessed the positioning of that self in a state of siege vis-à-vis the prospect of a quick, technologically assisted annihilation, and the figure painting of that century registered that threat in images of anxiety and anguish. I would submit that the new network assisted threat to subjective autonomy lies not so much in any portent of instantaneous demise so much as it would manifest itself as a kind of slow death by a thousand cuts of distraction leading to the point where autonomous subjectivity finds itself slowly dissolving into the position where all meaning is diluted out of existence. If this is indeed correct, than we can say with some certainty that Molesky’s new paintings are doing what the art of any time should do: chart the subtle psychological character of a fall into a new kind of oblivion, and report faithfully and even dramatically on the experiential consequences of that descent.